Talking to your Butcher

Don’t be intimidated, he’s a great guy and knows his meat!

These days it’s a rare luxury to be able to visit a butcher shop. We’re living in an era where about one in five meals is bought at a restaurant. So buying meat from a butcher is nearly a lost art, something largely reserved for chefs, die-hard smokers and grillers. Sadly its become the norm even as Americans are increasingly attuned to food sourcing and safety.

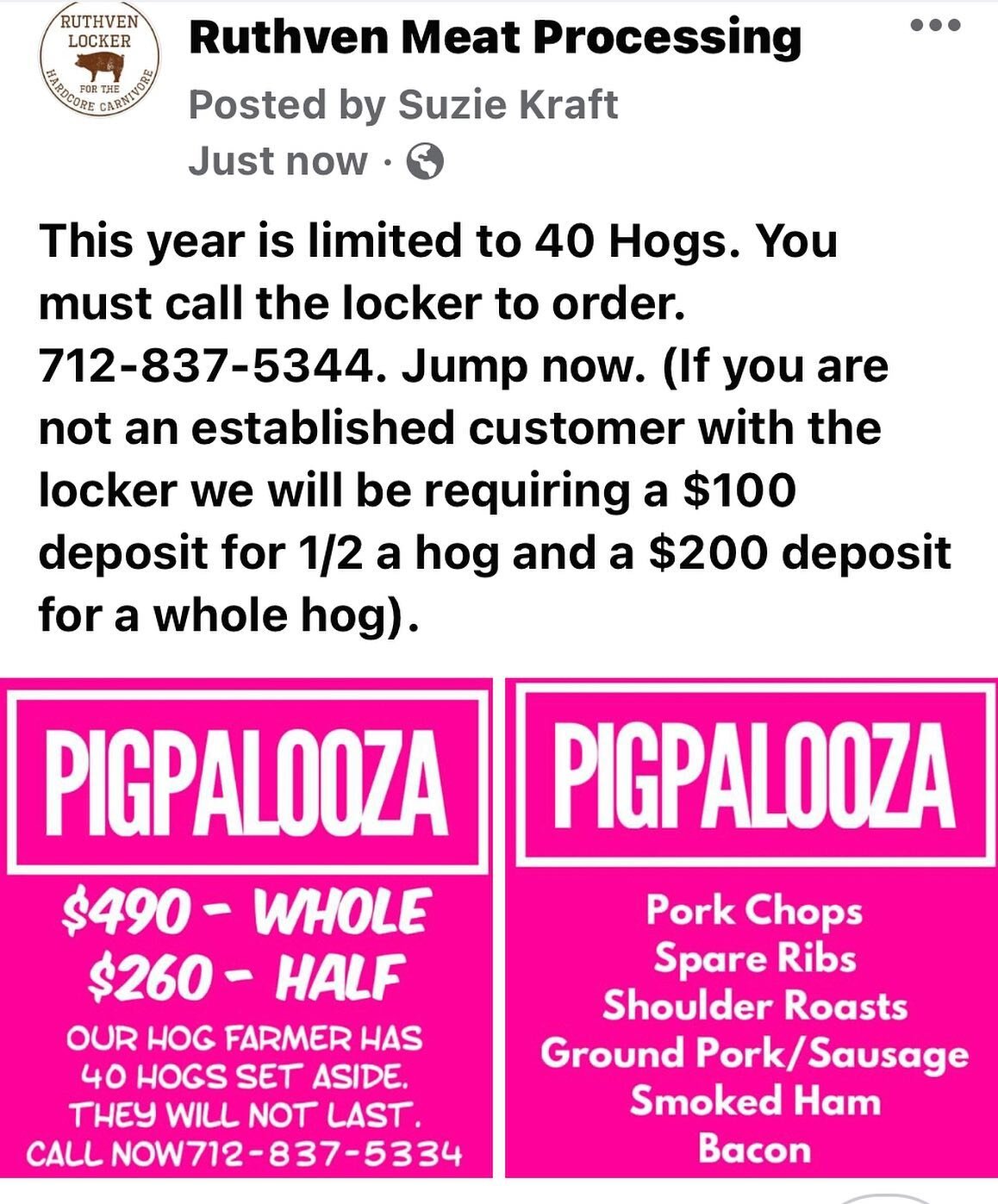

The corner butcher has been replaced by the conveniences of the modern supermarket meat counter. A shrinking industry keeps shrinking, with just under 5000 meat markets across the United States in 2018. Just five years earlier, there were more than 7,200. Despite those numbers there are consumers who are lucky enough to frequent a butcher.

As a Butcher’s wife, I’ve noticed that people truly miss the opportunity to talk to the “person behind the counter”. Not everybody wants to go to the grocery store and just pull something out.

I'm spoiled. I married into a family of Butchers with a meat locker. But it wasn’t that long ago that I felt super overwhelmed at the meat counter. I could get a fresh steak and italian sausage, but I couldn't figure out whether I needed a strip steak or a skirt steak. It was intimidating and embarrassing to ask. It was equally difficult to get real answers to questions about what animals were fed and where they came from. Too often, "It's natural," was the stock response. When I asked for details, I got blank, or suspicious, stares.

So I have been asked: How exactly should you talk with your butcher? Here are my tips:

Trust. With any service business, butchering is as much about relationships as meat. And butchers acknowledge more than a little nervousness on the customer's side of the counter. And more so as customers grow accustomed to lower supermarket prices, and visiting the meat store only on special occasions. When it comes to buying meat, a little knowledge seems to breed a lot of skepticism.

At our retail shop in Spirit Lake I’ll pick out the best steak and some customers will say, “no, no, no, no, no, I'll take that one." There's a certain mistrust of butchers, and I think it goes back to that old story about the butcher putting their thumb on the scale or wanting to get rid of the biggest cuts in the case first.

Nearly any question about meat is fair game. And tact is key. That comes from being a familiar face. You're more likely to get a good answer when it's clear you're not playing a game of “gotcha”. We know that loyalty works both ways.

Be prepared. This is easy. Know which meals you're shopping for and how many people. Look through your recipes before you leave the house; we will tell you which cuts you need for them.

Learn Your Cuts. Here's where the confusion really starts, but we are happy to help. Americans gravitate to certain expensive cuts like filet — which, among other things, tells your guests you're willing to spend top dollar. But a tenderloin cut may not be the most satisfying. It's not always the most flavorful cut. It's the most tender.

But tender doesn't necessarily mean better. Brisket and flank steak can be just as satisfying to serve, if you know how to draw out their flavors and soften them a bit.

Know Portion Sizes. We live in a nation of big steaks, and no one likes an empty serving platter. But consider that a standard restaurant portion is 8 ounces. Federal dietary guidelines consider a meat serving to be 2 to 3 ounces cooked. Fat and water are lost in cooking, but even a Big Mac tops out at just over 7 ounces, including the bun and toppings. Only you know how much your family or guests will eat. But tell your butcher how many people you're serving, and work out the amount you need.

Grades Aren't Everything. You've likely seen the USDA grades for beef used in the display case. They're useful as a quality guide, but only as a baseline. Grades primarily deal with the amount of intramuscular fat in meat. The more marbling, the higher the grade. Higher grades often have more fat and more calories than leaner meat. The three grades to look for are prime, choice or select, in that order. Prime may be the highest grade available, but restaurants just about have the lock on the prime beef supply and few butcher shops offer it. Not many people will know the difference if they're not butchers. Choice beef is perfect in my opinion, even for a fancy dinner. The best lamb grades are prime and choice, but they're rarely labeled in stores. Fresh pork can only graded as "acceptable."

Freshness: The Right Questions. Some items in a butcher shop should be as fresh as possible. Poultry, especially, goes into this category. Ask for the freshest steaks and you may get a “look”, because some red meat should be aged. A better question is, “Is this aged and how long have you aged it?” rather than “When did this come in?”.

Aging allows beef and lamb to soften as the tissue breaks down a bit. It makes the meat more tender and usually more flavorful. Many butchers pride themselves on aging. There's one big catch.

The most valued process is dry-aging: A side of meat is hung in a locker at temperatures just above freezing, sometimes for up to a month. But for decades, most U.S. meat has been "wet-aged." Meat sits in its juices — usually in a sealed plastic package — for a week or two.

Ninety-nine percent of the time, if a restaurant or butcher shop or supermarket says that they sell aged beef, chances are it's wet-aged.

If dry aging makes better meat, why not do it? For one thing, cost. Dry-aged beef develops a hard, often moldy rind that must be cut away before the meat is sold. The meat also loses a good share of its water weight, which heightens flavor but shrinks the meat. At our Locker we do not dry age as it is not permitted under the rules of our inspection level. If you want dry-aged, it should be aged between 20 and 30 days. And it will be more expensive.

Beyond the Label. Increasingly, consumers are drawn to marketing terms like "natural," which can be useful but often require more probing to understand just what they mean. "Natural" is the biggest fudge word around. Under USDA regulations, it simply means that no colorings, and generally no other additives, are used in meat. It says nothing about animal health or feeding. The key is to get detailed descriptions about animal-handling regimens. This is the moment when that trust factor often looms largest. Ask nicely. If someone doesn't know, ask which firms supplied the meat; suppliers should be able to answer. Be especially cautious of terms that highlight a specific practice, like "no growth hormones." Conventional beef may have been raised using hormones and antibiotics, but pork and poultry by law cannot be given hormones. So basically, a no-hormone label on pork is irrelevant.

My Meat Eats What? The meat industry has a whole range of marketing terms to describe animal feeding regimens. But here, too, vague words have crept in. "Organic" indicates rigorous standards, but has more to do with the quality of animal feed than what that feed consists of. Grass-fed doesn't indicate whether an animal was fed grass all the way to slaughter; many are finished on grain or corn. ("Grass finished" is more useful.) Vegetarian-fed simply indicates a farmer didn't use feed containing animal protein or byproducts.

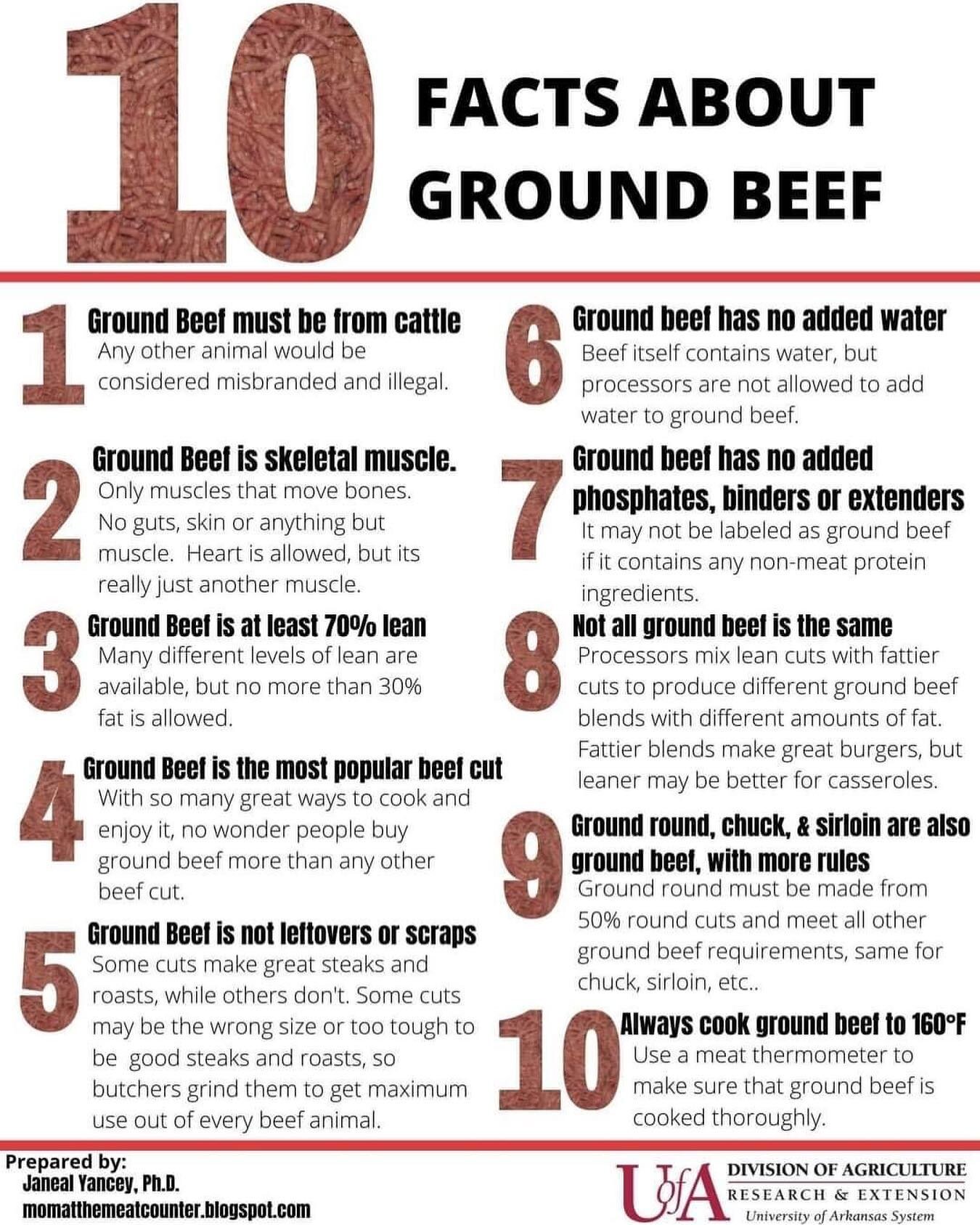

Ground Meat. A special treat of buying from butchers is that we sell freshly ground meat made right in our plant. Freshness isn't the only issue. We use cuts from just a few animals when we grind. When you buy prepackaged ground beef, up to 100 different cows could be in that grinding. The potential for contamination in that, it's high.

One Last Thing: Never be afraid to ask us questions! We love answering them!